The myth of Polish cavalry charges against tanks in September 1939

With the anniversary of the German invasion of Poland in 1939, I bring you an excellent article by Alberto Gómez Trujillo on one of the most widespread myths of World War II.

Charge to Glory

The Myth of Polish Cavalry Charges Against Tanks in September 1939

By Alberto Gómez Trujillo and Historical-Cultural Association Poland First to Fight

Translated by Elentir

The reason for the cavalry into the twentieth century

In 1939 cavalry was still one of the main weapons of the Polish Army; Indeed, it was considered as the elite of it, especially the units of Mounted Artillery. The cavalry regiments were the destination chosen by the majority of the best officers of each promotion.

The fact that cavalry survived as a substantial part of the army seemed so anachronistic in the 20th century, but it was due more to the conclusions drawn from experience in the last battles that took place on Polish territory than to questions related to the long equestrian tradition of the nation (that too).

World War I in the East had been fought mainly on Polish soil and had been a war of movements, contrary to what happened in the war of trenches of the front of the West. The cavalry could act effectively.

In the 1919-1920 war between Poland and Soviet Russia, cavalry had played a key role. In the broad plains of eastern Poland, the two Bolshevik armies of cavalry, the Konarmia of Ghay Khan (in the north) and Budionny (in the south), had advanced unstoppably flanking the Polish defensive positions. In the decisive Polish victory at the Battle of Warsaw, Polish cavalry had been determinant, and it would be again defeating the Konarmia of Budionny in Komarów, the last great battle of history exclusively fought by cavalry troops in which 1,500 Polish riders defeated 6,000 Soviets, causing them 4,000 casualties in exchange for 300 dead and wounded on the Polish side.

Battle of Komarów (Author: Jerzy Kossak)

In addition, during the 1920s and the first half of the 1930s the Soviet Union was considered the greatest threat to Poland, and the land of eastern Poland, mainly flat, but plagued by marshes and with scarce and primitive ways and roads, was much more suited to the movement of mounted troops than to the primitive and fragile vehicles of the time.

These considerations led Polish military planners to conclude that cavalry still had an important role to play in the defense of Poland. Germany did not pose a threat until after the equator of the 1930s, when the process of mechanization of the Polish Army began.

Battle of Mokra

The cavalry in September 1939

At the beginning of World War II the Polish Army had 11 brigades of cavalry, in addition to two others in process of mechanization quite advanced.

Each cavalry brigade ranged from about 6000-7000 men and consisted of 3 or 4 cavalry regiments, mostly Uhlans (lancers), a "Dywizjon" division of mounted artillery (the term Dywizjon in Polish actually refers to a company, because each one consisted of 3 batteries of 4 guns), a small armored unit formed by a squadron of tanks and one of armored cars, a bicycle squadron and another of engineers, and finally a battalion of fiflemen. Each cavalry regiment had about 800-900 men, and had a squadron of heavy machine guns, an antitank platoon and another cyclist.

At the end of the article there is an explanatory table of the organization of Polish cavalry brigades and regiments.

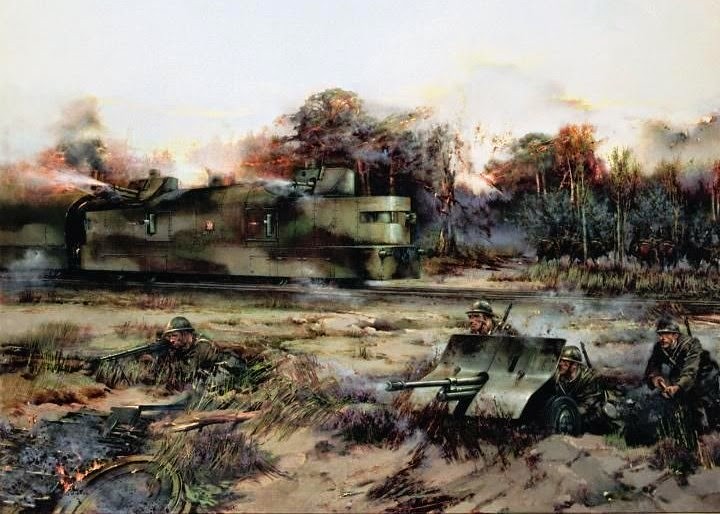

Battle of Mokra

Tactics in combat during the September Campaign

The Polish military manuals in 1939 no longer considered charges as a main resource of cavalry. In fact, the spear had been withdrawn in 1936 and was only used in parades and marches. The armament of the Uhlan was very similar the one of the Polish infantry of the time and the saber was conserved only like a weapon of last resort.

The function of the Polish cavalry was to fight like mounted infantry, acting like a mobile reserve, able to move and deploy quickly to go in support of the infantry, covering holes in the defense when necessary or clearing the way in the attack. For this, each regiment had 37 mm anti-tank guns (insufficient number), anti-tank rifles Wz35, light and heavy machine guns, etc.

Although the final outcome of the September 1939 Campaign is known to all, it must be said that cavalry performed very well generally, even in cases where it was faced against German tanks, without being exhaustive we will give some examples:

- On 1 September the Battle of Mokra was fought, in which the 4th Panzer Division was detained for a full day by the Wołyńska Cavalry Brigade. During the attack on the positions defended by the 12º Uhlan Regiment "Podolski", 4th Panzer Division lost about 40 cars and armored vehicles. When finally the Polish Cavalry had to retire, the following day, had suffered about 500 casualties against the 1,200 dead and wounded and 40 destroyed tanks of the Germans.

- Also the same of September 1st, during the Battle of the Woods of Tuchola, in the Pomerania corridor, the 20th German Motorized Division was stopped by the Cavalry Brigade "Pomorska", the head of the division arriving to request permission to retire before an "intense pressure of the cavalry".

Charge of the 19º of Uhlans in Mokra (Author: Edward Mesjasza)

Charge!

Once this point has been clarified, it must be said that there were charges of cavalry with the saber, during the brief September Campaign just over a dozen of them were recorded. They were punctual actions in which they had a clear advantageous position for the cavalry, or else the situation was already totally desperate. Usually these charges were against infantry units, never directly against armored units, and in most cases these charges culminated successfully for the attacking cavalry.

During the aforementioned Battle of Mokra, on 1 September, a charge of the 19th Uhlan Regiment of Wolynia (Wołyński) rejected the infantry units of the 4th Panzer Division as they attempted to flank the defensive positions of the Wołyńska Brigade.

In Janow, on 1 September, a squadron of the 11th Uhlan Regiment of the Legions, belonging to the "Mazowiecka" Cavalry Brigade, charged on a German cavalry unit and fled it after a brief collision in which Poles suffered about 30 casualties and Germans 40.

On 2 September in the Borowa aldéa, a squadron of the 19th Uhlan Regiment of Wolynia (Wołyński) charged against a German cavalry squadron, which escaped without accepting the clash ...

When on September 11 the 20th Uhlan Regiment "King Jan III Sobieski" of the "Kressowa" Cavalry Brigade was surrounded and destroyed in the Psary Forest, near Szymanów, Lieutenant Jan Burtow's squadron charged to breaking the siege, managing to escape to join the 22nd Uranian Regiment.

On the night of 11 to 12 September, the 11th Uhlan Regiment of the Legions and the 6th Infantry Regiment of the Legions were ordered to attack the city of Kałuszyn, which was occupied by German troops of the 1st Panzer Division, specifically By the 44th Regiment and the SS Regiment "Deutschland". The order to advance was misinterpreted and the squadron of Lieutenant Andrzej Żyliński launched the charge getting into the city despite losing 33 of its 85 men. The Polish infantry took advantage of the breach in the German defenses to enter the city and liberate it. The next day the city was in Polish hands and the 1st Panzer Division in retreat. Polish casualties are unknown, apart from the 33 Uhlans fallen during loading. The German casualties were 120 dead, 200 injured and 84 missing. Major Krawutschke, who commanded the 44th Infantry Regiment, committed suicide.

On 13 September a squadron of the 27th Uhlan Regiment "King Stefan Batory", under the command of Captain Boris Gierasiuk, after fleeing the Germans, charged them in their pursuit, reconquering the city of Maliszew in the process and doing numerous prisoners.

On September 15, during the Battle of Bzura, the 17th Uhlan Regiment "Wielkopolski" was ordered to occupy a cross of the Bzura river in the area of Brochow to establish a bridgehead on the east bank of the river. For it, several squadrons charged against the positions of the German infantry and after reaching them they dismounted and fought on foot.

Charge of the 14th Uhlan Regiment in Wólka Węglowa (Museum of the Army, Warsaw)

On September 19, about 1000 riders from the 14th Uhlan Regiment of Jazłowiec and the 9th Uhlan Regiment of Malopolska (Podolska Brigade), retreating to Warsaw with the Poznan and Pomerania armies, successfully charged into Wólka Węglowa, near the forest Of Kampinos, against the German troops that interposed between them and Warsaw. It is estimated that the German forces consisted of about 2,300 men and some 40 tanks of the 1st Panzer Division, as well as artillery and cavalry. The Germans were surprised by the night charge and the Polish cavalry managed to break the lines, being the first units of the Poznan Army that managed to arrive at the capital to contribute to its defense. Polish casualties were very high, as 105 lancers died and another 100 were wounded, or 20% of the participants. For its part the Germans lost about 120 men between dead and wounded.

During the battle of Kamionka Strumiłowa, on September 21, the third squadron of the 1st Cavalry Division (an improvised unit) charged the German infantry when it was preparing to attack positions of the Polish infantry, the Germans abandoned their positions and withdrew.

Between 21 and 22 September the remains of the 5th, 20th and 28th infantry divisions, as well as the cavalry group of Major Josef Juniewicz, composed of remnants of the 12th Uhlan Regiment "Podolski" and 21st Uhlan Regiument "Nadwiślański" of the "Wolynska" Cavalry Brigade, the 6th Mounted Rifle Regiment of the "Kressowa" Brigade and the 6th "Dywizjon" Mounted Artillery of the Podolska Brigade, attempted to retreat from the Kampinos forest to the fortress Of Modlin. Between them and their destination were two German regiments of the 18th Infantry Division supported by artillery, tanks and the Luftwaffe. Polish forces totaled about 5,000 men, of which 1,500 were cavalry and had only 6 guns.

The Polish soldiers attacked with great fierceness and managed to break the first of the three defensive lines that had prepared the Germans, but the attack stopped before the second. Major Juniewicz's riders charged against the German lines, Major Juniewicz dying, as well as 90% of the officers and 60% of the soldiers who took part in the charge.

The riders of the 6th "Dywizjon" mounted Artillery headed the charge that opened the way to Warsaw to the rest of the unit. In the Battle of Łomianki 800 Polish soldiers died and more than 4,000 were wounded. German casualties are not known.

Still on the 23rd, when all was lost, the 25th and 27th Uhlan Regiments, belonging to the Cavalry Brigade "Nowogrodzska", which was heading south to reach the Romanian border, took part in the Battle of Krasnobrod. During the same the first squadron of the 25th Uhlan Regiment made a charge that, in addition to allowing the brigade to reconquer the city of Krasnobrod and to capture to the staff of the 8ª German Infantry Division, rejected a counterattack of the German cavalry. However, during the charge, the squadron entered a zone beaten by German machine guns and was practically annihilated, suffering 35 wounded and 26 dead, among them its chief Lieutenant Tadeusz Gerlecki. The German casualties were 47 dead, 30 wounded and about 100 prisoners.

Charge of Husynne (Author: Stanislaw Bodes)

On the same day, a Polish cavalry unit, consisting of the reserve squadron of the 14th Uhlan Regiment of Jazłowiec and a mounted squadron of the Warsaw Police, along with a battalion of mortars, was surrounded by the 81st Infantry Division of the Red Army in the village of Husynne, in the valley of the river Bug. Supported by mortar fire, 400 Polish riders charged the Soviets to try to break the siege. The Soviet infantry undertook the flight suffering heavy losses, but behind the hills were Soviet armored units that surrounded the Poles and after a fierce battle forced them to surrender. Of the 500 Polish soldiers who took part in the battle, 143 died and 139 were wounded, the rest was captured. According to the testimony of Corporal Włodzimierz Rzeczyck, of the 14th Uhlan Regiment, the Soviets killed 25 Polish prisoners of war after the battle. Soviet casualties totaled 200 men.

The last charge of the September Campaign was led by the 27th Uhlan Regiment "King Stefan Batory", which charged twice against a German infantry battalion defending the town of Morańce. Both charges were rejected and 20 Uhlans died, but the Germans were forced to send messengers under a white flag to negotiate the terms on which they would abandon the village.

The myth is born

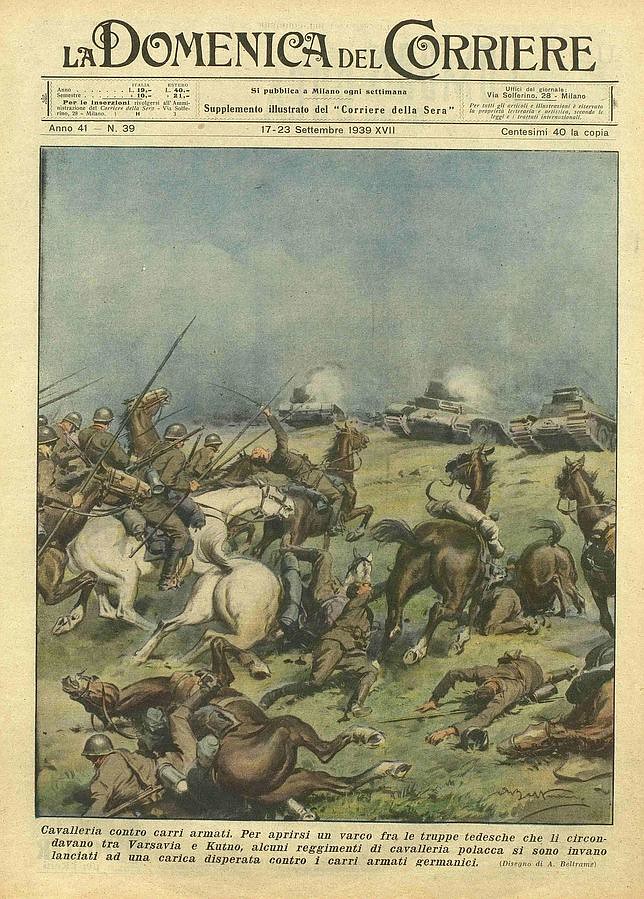

Frontpage of La Domenica del Corriere, with an imaginative illustration of the charge of Krojanty

The legend is born on September 1, when in the village of Krojanty, on the edge of the forest of Tuchola, the 18th Uhlan Regiment discovered the 20th German Division bivouac. Seeing a favorable situation, Colonel Martarlerz, commander of the Regiment, launched a charge with 2 squadrons of the same (about 200 men). The Germans, surprised, left literally running in disarray and the Poles fell on them with sabers. Fortunately for the Germans, a reconnaissance unit equipped with auto-machine guns and armored vehicles appeared on the scene during the fray, and with their machine guns and cannons they rejected the Poles, who had to retire to the forest with many wounded and leaving 40 dead in hhe terrain, including the commander of the Regiment.

Although armored vehicles took part in the action, this can hardly be considered a deliberate charge against the tanks, since they entered the scene once the charge began.

The next day several journalists came to the scene and the Germans showed them the corpses of the horsemen and their saddles, explained to them that they had been killed by the armored vehicles, and they wrote for their media that the Polish lancers charged insanely against the tanks. One of those journalists, Indro Montanelli, in his chronicle for "Il Corriere della Sera" described the events as a sublime act of heroism of the Poles.

The truth is that, although General Heinz Guderian also speaks of these charges against the tanks in his memoirs, these never happened.

The myth is consolidated

But the myth flourished in historiography. Somehow, because everyone was convenient and attractive, depending on each point of view ...

On the one hand, to the German propaganda it served to show the world how the Poles had underestimated the power of German arms while, on the other hand, yo the Western allies it served to justify their inaction and lack of assistance to Poland in September 1939 shielding himself in the poor performance of an army so old and badly commanded that it was able to charge with spears against tanks.

The Soviets and the postwar communist Polish government exploited the myth to discredit the institutions and leaders of the 2nd Polish Republic, arguing that they had not prepared the defense of the country and they had not even scrupled to send their soldiers to death without sense ...

This was of vital importance for an unpopular regime which, even in a war-torn country, could not have been sustained without the backing of the Soviet Army, and which attempted at all costs to denigrate the pre-war regime, which was the one the majority of Poles considered legitimate.

The paradox is that, for quite different reasons, this myth came to appeal to non-communist Poles, loyal to the Polish Government in London and even today's Polish, and many still believe it true. Since if one looks from a romantic and patriotic perspective (and the Poles are both), they are acts of sublime heroism ...

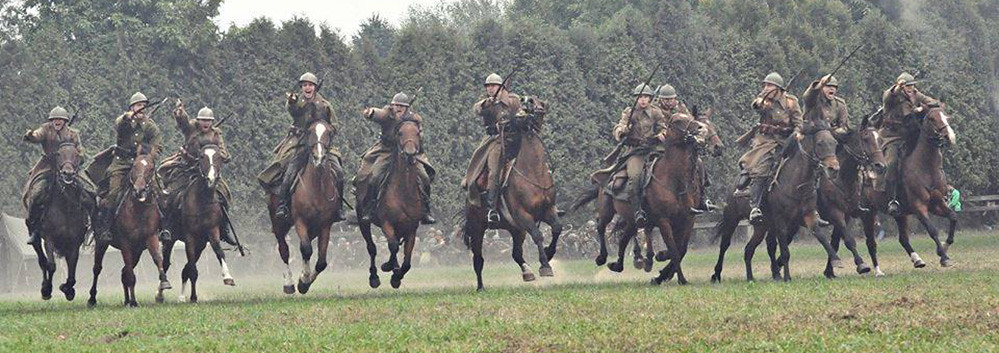

Charge of Boruszko

Epilogue

It is the afternoon of March 1, 1945; 1st, 2nd and 6th Polish Infantry Divisions, supported by the T-34/85 of the Polish Armored Brigade "Heroes of Westerplatte", dislodge the 163rd German Infantry Division, heavily fortified in the village of Schoenfeld in Pomerania (today it is part of Poland and is called Żeńsko, then Borujsko in Polish).

The attack is bogged down by the difficulty of the terrain, and the fields of mines and ditches and the infantry and tanks fail to break the German defenses.

At the edge of the forest there are two squadrons of the 3rd Ulhan Regiment of the 1st Polish Cavalry Brigade "Warszawska" and two mounted artillery batteries of the 4th Polish Cavalry Brigade, in total about 220 horsemen, form in line, draw sabers and are thrown to the charge.

Five and a half years have passed since the last charge of Polish cavalry and World War II is nearing its end. Like shadows of the past, galloping riders, who wear uniforms almost identical to those of their ancestors in 1939, pass between the infantry and the T34 tanks, cross the no man's land and take advantage of the confusion and surprise, enter the village followed by the infantry. After a fierce hand-to-hand combat Schoenfeld is conquered.

In Borujsko's charge 7 Uhlans were killed and 10 wounded, total Polish casualties in the battle were 147 dead and 294 wounded, the Germans had more than 500 dead and 50 prisoners.

| Order of Battle of a Polish Cavalry Brigade in 1939 (6000 - 7000 men depending on the number of regiments) |

|

| Cavalry Regiments 3 or 4 per brigade. The usual were brigades of 3 regiments, each of about 900 men. |

|

| Mounted Artillery Unit “Dywizjon” | 4 Batteries of 3 or 4 guns of 75 mm |

| Armored Unit | Tank Squadron (12/13 tanks TK3-TKS) Armored car squadron. (8 armored cars Wz34 or Wz 29) |

| Riflemen Battalion | |

| Headquarters Units |

|

Cavalry Brigades in 1939

- Cavalry Brigade “Krakow” (barracks in Krakow), under the command of Brigadier General Zygmunt Piasecki.

- Cavalry Brigade “Kresowa” (barracks in Brody), under the command of Colonel Stefan Hanka-Kulesza.

- Cavalry Brigade “Mazowiecka” (barracks in Warsaw), under the command of Colonel Jan Karcz.

- Cavalry Brigade “Nowogródzka” (barracks inn Baranowicze), under the command of Brigadier General Władysław Anders.

- Cavalry Brigade “Podlaska” (barracks in Białystok), under the command of Brigadier General Ludwik Kmicic-Skrzyński.

- Cavalry Brigade “Podolska” (barracks in Stanisławów),under the command of Colonel Leon Strzelecki.

- Cavalry Brigade “Pomorska” (barracks in Bydgoszcz), under the command of Colonel Adam Zakrzewski.

- Cavalry Brigade “Suwalska” (barracks in Suwałki), under the command of Brigadier General Zygmunt Podhorski.

- Cavalry Brigade “Wielkopolska” (barracks in Poznań),under the command of Brigadier General Roman Abraham.

- Cavalry Brigade “Wileńska” (barracks in Wilno), under the command of Colonel Konstanty Drucki-Lubecki

- Cavalry Brigade “Wołyńska” (barracks in Równe). under the command of Colonel Julian Filipowicz.

|

Don't miss the news and content that interest you. Receive the free daily newsletter in your email: |

- Most read

- The 'hole' without civil flights around Paris during the opening of the Olympic Games

- Stunning footage of the F-15QA Ababil in flight recorded from its cockpit

- The firearms used by the Pontifical Swiss Guard, the smallest army in the world

- The most distant deployment of the Spanish Air Force in Australia and New Zealand

- Eurofighter vs F-35: the opinions of professional pilots on these advanced fighters

- The first photo of an F-16 fighter with Ukrainian insignia and the details it has revealed

- This is the driver station of an M1 Abrams tank and the impressive start of its engine

ES

ES

Opina sobre esta entrada: