The story of Captain Wilhelm Hosenfeld: a German catholic who helped save Poles

On this day, as on today, August 13, 1952, a just man died during his captivity in a Soviet concentration camp in Stalingrad. His name was Wilhelm Hosenfeld and this is his story.

A German patriot born into a devout Catholic family

Wilhelm Adalbert Hosenfeld, usually known as Wilm, was born on May 2, 1895 in Mackenzell, a small town in the state of Hesse, then part of the kingdom of Prussia. He grew up in a very devout Catholic family, being the fourth of six children, and grew up in a conservative and patriotic environment. His father was a teacher in a catholic school and he tried that the small Wilm was educated in the sense of the charity, something to which contributed his militancy in Catholic Action. The young Hosenfeld wanted to follow in his father's footsteps and become a teacher, but in July 1914, when he was 19 years old, the First World War broke out. Wilm participated in the fight as an infantry soldier, being seriously wounded in 1917 and receiving the Second Class Iron Cross. After his convalescence, he returned to his hometown, beginning to work as a teacher in 1918. Two years later he married Annemarie Krummacher, a young Protestant of pacifist ideas and daughter of the impressionist painter Karl Krummacher, a man of liberal ideas. Annemarie and Wilm had two sons and three daughters: Helmut (born 1921), Anemone (1924), Detlev (1927), Jorinde (1932) and Uta (1937).

The first aid of Hosenfeld to the Poles in 1939

Wilm's patriotic ideas made him feel attracted to national-socialism in 1933, joining the NSDAP in 1935, although he did not share the anti-Semitism of the Nazis nor their hostility to the Catholic Church. Like many Germans, he saw the Nazis as a movement of national recovery after the humiliating German defeat of 1918 and the serious crisis of the postwar period. Wilm was again called up in August 1939. When Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, Wilm was 44 years old. He was sent to Poland in the middle of that month with the rank of sergeant as part of an infantry battalion belonging to the Landwehr, a militia that framed men aged between 35 and 45 years. At the end of September 1939 he was sent to Pabianice, participating in the construction and custody of a Polish prisoner of war camp. Wilm was a kind and gentle man, who was not afraid to show himself talking to Jews and picking up Polish children. On one occasion, when he was riding a bicycle near Pabianice, he met a young Jewish girl who was running along the road. When asked where she was going, she answered scared, telling him she was pregnant and that her husband is imprisoned in the prison camp. He was going there to ask for his release. Wilm wrote down the prisoner's name and said, "Your husband will be home again in three days." So it was.

On another occasion, Wilm learned that the Gestapo, the fearsome secret police of the Third Reich, had gathered several men, including the brother-in-law of a Polish priest. They were taken to a forced labor camp and the cleric's brother-in-law was to be executed. Wilm saw the truck with the prisoners and told an SS officer that he needed a man for a job. From among the prisoners who were in the truck, Wilm chose the brother-in-law of the priest, the one who was going to be shot, pretending to choose at random. Thanks to that, he saved the man's life.

The radical distancing of Hosenfeld from Nazism

In December 1939 he was sent to Węgrów. By then Wilm was already disenchanted with Nazism, witnessing the atrocities perpetrated by his countrymen against the Poles, both Catholics and Jews. In his letters to his wife, and in spite of the risk he was running -owing to the post-war censorship- he expressed his disgust for communism and nazism, which he considered equally criminal ideologies (remember that Germany and the USSR had divided Poland in 1939, committing numerous atrocities in their respective occupation zones). He also expressed in these letters his shame for the crimes committed by the Germans in Poland:

"You have to ask yourself how it could have happened that in our nation we have such a degenerated scum. Have they freed criminals and disturbed people from psychiatric hospitals that function like rabid dogs? Unfortunately, no, these are the people who occupy high positions in our country."

His faith in God gave him strength in the midst of this horror, and also encouraged him to help the persecuted. In Sokołów Podlaski he began to help the Poles who were being deported to Germany. In June 1940, as a lieutenant, Wilm was sent to Warsaw with the 660th Battalion of the Guard. Once there, his sympathy for the Poles led him to learn the Polish language. Being a Catholic, he often went to Mass in a Polish church and received Communion. Soon he began to provide false documents to some Poles, including Jews, managing to save their lives. He often employed them in the sports school of the Wehrmacht that Wilm directed in Warsaw. On September 1, 1942, Wilm wrote a letter to his wife showing himself convinced that the German crimes in Poland were a consequence of God's estrangement: "without him we are only animals in conflict, we believe that we must destroy each other. We will not listen to the divine commandment: «Love one another»."

"We do not deserve mercy; we are all guilty"

On June 16, 1943, Wilm wrote in his diary, horrified, referring to the crimes committed by the Germans during the liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto: "Innumerable Jews have been killed like that, without any reason, without meaning. It is beyond understanding. Now the last remains of the Jewish inhabitants of the ghetto are being exterminated. A SS Sturmführer boasted about the way they murdered the Jews as they ran out of the burning buildings. The whole ghetto has been destroyed by fire. These brutes think that we will win the war in that way. But we have lost the war with this frightful mass murder of the Jews." And he added: "We do not deserve mercy; we are all guilty."

Wilm's repulsion at the atrocities of the Germans made him feel a mixture of indignation and shame. On August 13, 1943, he wrote in his diary: "It is impossible to believe all these things, although they are true. Yesterday I saw two of these beasts on the tram. They held whips in their hands when they left the ghetto. I'd like to throw those dogs under the tram. What cowards we are, wishing to be better and allowing all this to happen. Because of this, we will also be punished, and our innocent children after us, because by allowing these bad actions to happen, we are partakers of the guilt." On December 5, 1943, he wrote: "Our entire nation will have to pay for all these errors and this unhappiness, all the crimes that we have committed. Many innocent people must be sacrificed before the guilt over the blood we have incurred can be extinguished."

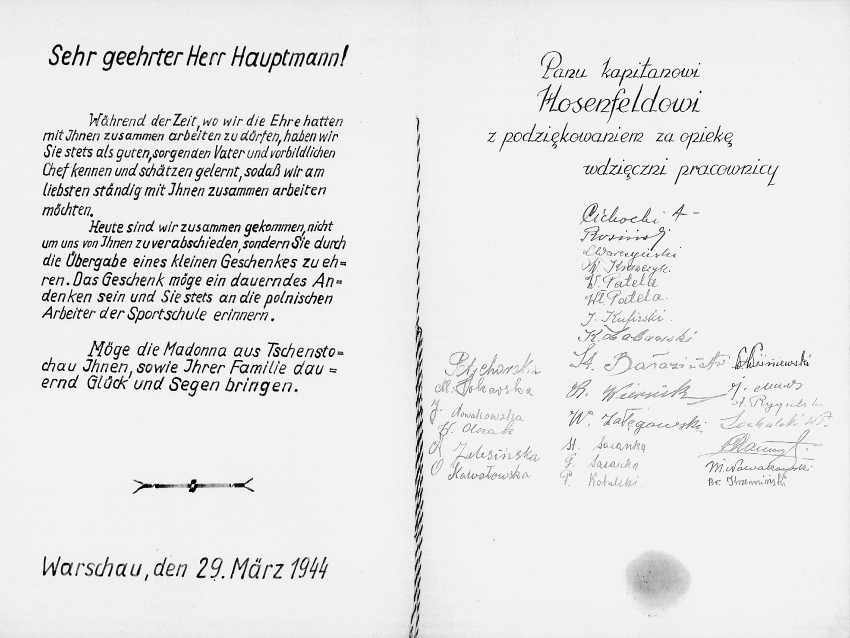

An image of the Virgin of Czestochowa as a token of appreciation

Another person Wilm helped during the war was Leon Warm, a Jew who had escaped from the Treblinka extermination camp. The German officer protected him and got him fake documents, risking his own life with it. Wilm also saved the life of the priest Antoni Cieciora, a member of the Polish resistance who was on the wanted list by the Gestapo. Wilm gave him a job after providing false documents. On March 29, 1944, the 27 Poles whom Wilm had employed at the Wehrmacht sports school in Warsaw signed a thank-you document to the man who had helped them. Next to the document they gave him an image of the Virgin of Czestochowa, because they knew that the officer was Catholic. This shows the popularity that Wilm had among his Polish acquaintances due to his humanity.

The admiration of Hosenfeld for the members of the Polish resistance

After the outbreak of the Warsaw Uprising on August 1, 1944, Wilm served in the German counterintelligence, dealing with the interrogation of members of the Polish resistance and Soviet soldiers. Wilm demanded to treat the prisoners in accordance with the norms of the Geneva Convention, against the order of Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS, to treat them as "bandits and rebels". During the interrogations, Wilm tried to help members of the Polish resistance, whose courage he admired. That same month, Wilm sent his wife his diary (in which he recounted the atrocities he had contemplated) hidden in a package of clothes.

The meeting that made him famous: the Jewish pianist Władysław Szpilman

After the end of the Warsaw Uprising, on November 17, 1944, the then Captain Hosenfeld arrived at an abandoned building on Niepodległości Avenue 223 in Warsaw. There he had an unexpected encounter that would take him to fame many years later: Władysław Szpilman, one of only 20 living Jews left in Warsaw after the Uprising. Szpilman was a pianist who had become famous playing for Polish Radio before the war and who had been sheltering there since August 1944. When Wilm discovered him, Szpilman thought he was going to arrest him, but instead, when he told the German officer who was a pianist, Wilm asked him to play something on a piano that was on the ground floor of the building. Szpilman played Nocturne nº20 in C sharp minor of Chopin, the same composition he was playing on Polish Radio on September 23, 1939 when a bombing interrupted the broadcast. You can see in this video Szpilman himself playing that same piece in 1997 at his home in Warsaw:

Wilm helped the pianist to improve his hiding place and brought him food frequently, even giving him his coat to protect him from the freezing temperatures of the Polish winter. Szpilman did not know the name of the German officer until 1950. He told what happened in his memoirs, entitled "The death of a city" and published in 1946. In the book, the pianist referred to the German officer as "the only human being in uniform German that I knew." The communist regime censored the book, making Wilm Austrian, since it was unacceptable for the Stalinists to present a German starring in a humanitarian act.

Finally translated into 35 languages later, Szpilman's book inspired Roman Polanski to shoot his film "The Pianist" (2002) about Szpilman's experiences in World War II. In the film, the role of Wilm was made by the German actor Thomas Kretschmann. This film served to make Captain Wilhelm Hosenfeld known all over the world. Interestingly, in the scene of the meeting between Wilm and Szpilman in the film, the pianist does not interpret Nocturne No. 20, but the Ballad No. 1 in G minor Op.23:

Captivity, torture and death of a just man

On January 17, 1945, Wilm was taken prisoner by the Soviets in Błonie, a Polish town 30 kilometers west of Warsaw, along with the men of the company he led. At the end of January 1945, the Polish violinist Zygmunt Lednicki went through the fence of a Warsaw detention center. Wilm, was there prisoner, and asked him from the other side of the fence if he knew the pianist Szpilman. Lednicki said yes. "He should save me, I implore you," the officer pleaded. But by then Szpilman still did not know the name of the German officer who had helped him, so he could not locate him.

In a letter written to his wife, who lived in West Germany, in 1946, Wilm indicated the names of several Jews whom he had helped - among them Szpilman -, seeking their intercession to secure his release. In 1947 he suffered the first of a series of strokes, spending long periods in the infirmaries of the prison camps where he was held. In 1950 a Soviet military court in Minsk sentenced him to 25 years in prison for war crimes for the simple fact of being a German officer. Władysław Szpilman, Leon Warm and others whom Wilm had helped asked for his release, but the Soviets refused. The German captain suffered frequent torture and brutal interrogation at the hands of the Soviets. As I have pointed out, Wilm died on August 13, 1953 in Stalingrad, shortly before ten o'clock at night, because of a ruptured thoracic aorta, possibly because of a torture session. He was 57 years old and physically and mentally shattered.

The recognition of Israel and Poland

After the death of Wilm's widow, Annemarie, in 1998 her daughter Jorinde found in the attic of her house more than 600 letters from her father to her mother and children, as well as several notebooks. These documents were published in 2004. In 1998 the name of Wilhelm Hosenfeld was added to the German edition of Szpilman's memoirs, finally identifying the German officer half a century later, thanks to an investigation carried out by Wolf Biermann. That same year, Szpilman requested Yad Vashem, the Israeli institute of the Holocaust memory, recognition for Wilhelm Hosenfeld as "Righteous Among the Nations", the highest distinction of the State of Israel to the non-Jews who helped save Jews, but the false accusations of war crimes made by the Soviets against the German officer blocked the appointment. After the death of Szpilman in the year 2000, his son Andrzej continued fighting to obtain that recognition for Hosenfeld. Finally, on February 16, 2009 Yad Vashem announced the awarding of that recognition to Wilm Hosenfeld. On June 19, 2009, Israeli diplomats handed over Detlev, one of Hosenfeld's sons, the official appointment of his father as "Righteous Among the Nations."

Poland also recognized the German officer who had helped save the lives of Poles in World War II. In October 2007, the then President of the Polish Republic, Lech Kaczyński, handed over to Detlev Hosenfeld the Commander's Cross of the Order of Poland Restituta - one of the highest Polish decorations - in his father's name, on behalf of posthumous. In addition, on December 4, 2011, a plaque was discovered in Polish and English in the Niepodległości 223 Avenue building, the place where Hosenfeld met Szpilman, commemorating that meeting and the help provided by the German officer. The inauguration of the plaque was attended by one of Hosenfeld's daughters, Jorinde, and Andrzej Szpilman, the pianist's son.

---

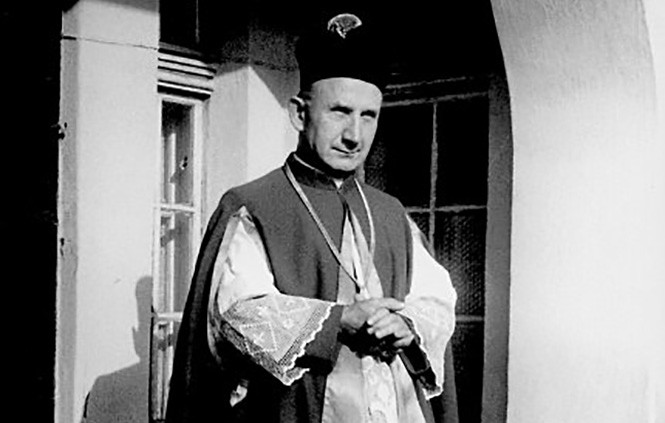

(Main photo: Spiegel.de / Private archive of the Hosenfeld family. Wilm Hosenfeld in East Prussia in 1940)

|

Don't miss the news and content that interest you. Receive the free daily newsletter in your email: Click here to subscribe |

- Most read

- The Pegasus case and how it could end with Pedro Sánchez due to a decision by France

- The ten oldest national flags in the world that are still in use today

- A large collection of Volkswagen cars hidden in an abandoned mine in Switzerland

- The United States Army shows its electric bicycles for reconnaissance missions

- Lenin: numbers, data and images of the crimes of the first communist dictator

- The German media Der Spiegel destroys Pedro Sánchez for his farce after having defended him

- NATO highlights and shows the 'air power' of the Spanish aircraft carrier 'Juan Carlos I'

ES

ES

Comentarios:

Roger Long

It is sad to know that a man who helped so many, during a terrible period, could not be saved himself, once the war was over.

19:22 | 16/12/19

itasara

I watched the movie, «The Pianist» which was so hard to watch in parts. Then I looked up this biography on Wilm Hosenfeld and indeed he was one of the righteous gentiles. I didn’t know anything about him til now. This too was a sad story. His heart was in the right place and it was unfortunate that in the end he was not saved or recognized in his lifetime for those whom he saved. It makes me even sadder to see this rise in anti-semitism in the 21st century. If Hosenfeld was alive now he would be out there on the side of justice and speaking out against antisemisim.

6:22 | 23/02/20

L. Kreusch

I have heard about The Pianist and wanted to see it. It such a sadness to know the suffering of many, and those who helped but could not be helped. The tragedy is that Wilm Hosenfeld died believing he had been forsaken. Not all stories have happy endings but must be told so that we know there will always be those who are righteous and humane in the face of evil. Such an honor to have a little glimpse into the character of a beautiful soul.

18:55 | 10/04/20

Simon McQuillan

Just watched the pianist and truly touched/saddened by the story of Wilhelm Hosenfeld. I am a grown man who was moved to tears by the accounts written here. Saved so many life’s knowing his could be lost. He was compassion in action!

It played on my mind that his name was not given to the pianist, Mr Szpiliman and that he could have been saved. Did he die believing no one was trying to reach out to him and help him?

Truly moved!

I would love to read more on this great man and see more recognition he deserves. Would love to contact the children of this great man and shake their hands/hug you.

19:18 | 24/05/20

Oskar

Izaak Stolzman aka Zdzisław Kwasniewski, Soviet criminal, NKVD colonel in the late 1940s and the beginning 50s, on the order of the NKVD authorities, oversaw and coordinated the criminal activities of poviat and municipal public security offices in Drawsko, Białogard, Szczecinek, Wałcz, Kołobrzeg, Połczyn, Jastrów and Okonek.

He also participated in the crimes of the Public Security Office in Gdańsk, Słupsk, Szczecin, Ustka, Koszalin and Elbląg.

After the Soviet invasion of Poland, Stolzman commanded the NKVD units in 1945-1947. committing genocide on German prisoners of war, Swedish sailors, AK soldiers, NSZ, and other armed formations.

He died in 1990.

17:55 | 3/06/20

Bruce Goff

Hosenfeld, in my opinion, is truly one of the finest and greatest men who has ever lived on this earth.

I’m so glad that Yad Vashem has recognized him as righteous among the nations.

19:30 | 30/07/20

Ron

HOSENFELD

On earth as in heaven …

Defeated Kaiser Reich …

Versailles …

Homeland chaos … reparations … lands and lifeline lost.

Then a madman’s promise – squeezed no more by victors –

the chorus of Heil for work and future,

reclaiming ours and demanding more … lebensraum … revenge …

Waffen, Panzers, Wehrmacht, Luftwaffe, Kriegsmarine .

Our Fatherland … Pride restored

and again the young to battle, total war for Third Reich adored.

A hook’d cross of life betrayed by diabolic intent.

Evil’s shadows … tentacles rapidly reaching … lightning blitzkrieg … surrendering mercy.

Mackenzell teacher, family and Faith, proud Prussian

with uniform pressed and proper … and Hauptmann rank

witnessing smashings and bashings, starving and killing innocents

Warsaw and ghetto Hell!

What is Your Will …?

On earth as in heaven … His prayer is my hoping.

God’s silence pleading mercy.

Loving God and neighbour … always higher and deeper

than Caesar’s commands.

Übermensch , arbeit macht frei , Juden und Polen exterminating in horrid poison chambers.

But all are God’s children … no junk.

His Mercy crying dry and helpless tears.

The Star on filthy rags hanging shamefully on skeletons barely living. No dignity left …

Our Cross of life in hiding … drawing me to them … our prayer … holding high Hoc est …

His Body receiving

becoming bread … a coat

an altered ID

a chance of hope for life

a pianist, Jew

a father, a mother-to-be, a child to hold and hug, Pole

a priest, soldier, underground struggling for light.

I am His Body, their body … fractured.

But hubris … pride and arrogance, plunder, torture, murder … is our sacrilege

desecration of life by rabid dogs

for we forced You out … God verboten !

Oh God!

Can we be forgiven? Merit Your Mercy from of old? Wail for our inhumanity?

Can this saviour now be saved?

Defeated Führer Reich …

Apocalyptic landscapes …

Unconditional surrender … no mercy …

Imprisoned, tortured, hungered … Mistaken for Abwehr, fearing Red revenge.

Family and Faith and Heimat photographed.

Broken Prussian now in rags with number; cold and endless; yelling orders; numb.

No mercy … No God here

in Stalingrad Camp Hell!

What is Your Will …?

On earth as in heaven … My prayer is my hoping.

My family … becoming what I cannot share

My pianist … touching keys that sing of liberty and love and light

My Polish child … maybe father or mother now remembering a dangerous kindness

My captors … fathers and sons obeying Koba Tyranny.

Yearning freedom … Home and school and land …

God’s silence … His Body’s absence … No cross of life to wear … Tears my bitter end …

Mercy awaiting!

My name Wilm Hosenfeld forgotten …

but Leuphana award

Polonia Restituta

Vad Yashem.

Verily

to reflect

to live: Amen … Your Will be done on earth as in heaven.

10:34 | 16/10/20

Sapeta

Thank you, for composing an insightful poem to honour a great human being.

Blessings to all those individuals like Wilm who walked among fellow human beings serving humanity through their good deeds.

0:16 | 23/10/20

Kevin Phillips

This movie was so moving and yet so tragic. Out of all that was bad was a gentle soul who loved life and wanted others to live. Wilm Hosenfeld is truly knows what compassion is all about. He is dead now but his action teach us that we yi can always strive to be human

And have compassion. God bless you Wilm.

15:25 | 23/08/21

Opina sobre esta entrada: