The story of the Spanish volunteers who fought to liberate Hungary from the Turks

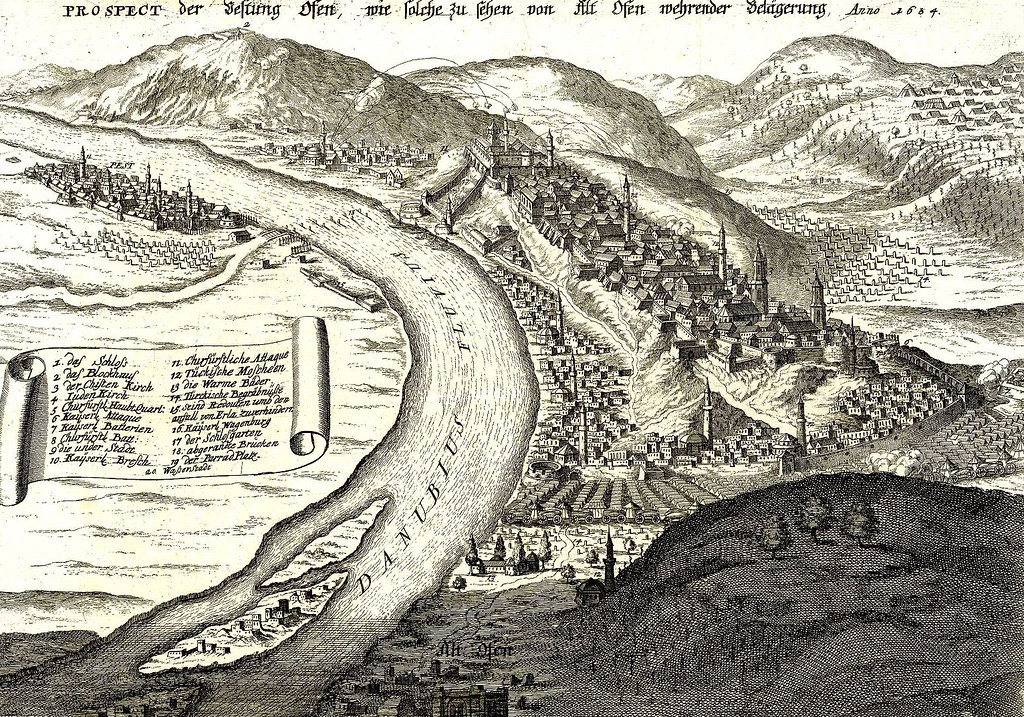

Such a day as today, on September 2, 1686, the city of Buda (today part of Budapest, capital of Hungary) was liberated after 145 years in the hands of the Turks. A Spanish force fought there.

The war against the Ottomans: from the Battle of Lepanto to the Siege of Vienna

In 1571, the Kingdom of Spain, the Papal States, the Republics of Genoa and Venice, the Duchy of Savoy and the Order of Malta had founded the Holy League to curb the expansionism of the Ottoman Empire by Europe. That same year, this Christian coalition defeated the Turks at the Battle of Lepanto. However, that Islamic empire continued to cast its shadow across Europe for more than a century. In 1683 a huge Turkish army invaded the Holy Roman Empire, conquering Belgrade in May and arriving at the gates of Vienna in June. That could have been the end of Christian Europe, but a new Holy League was formed, this time with the participation of the Papal States, the Holy Empire and the Polish-Lithuanian Republic. Moved by the defense of the Catholic faith, the King of Poland, Jan III Sobieski, and his winged hussars - the best cavalry of the time - came to the aid of Vienna and the Turks were defeated in September.

The Christian counteroffensive of the Holy League

After the Ottoman defeat in Vienna, Christians went on the counter-offensive, encouraged by Pope Innocent XI. The Holy League joined the adhesions of the Order of Malta, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany and the Principality of Moscow. Much of the Kingdom of Hungary was still in Turkish hands. Its capital, Buda, had been conquered by the Turks in 1541, so that the court had to move to Bratislava. The following year of the Siege of Vienna, in 1684, the Holy League went to Buda, with the objective of besieging it and liberating it, but it did not succeed, being obliged to retire with numerous casualties. But this defeat did not discourage the Christian forces. The humiliating defeat of the Turks before the gates of Vienna had excited people from all over Europe, who were willing to take up arms to expel the Ottomans from the continent.

Thousands of Spaniards went to Hungary to fight the Turks

By that time, the Spanish Empire had already begun its decline, bled by the disastrous War of Flanders. The previously invincible Spanish Tercios, the best infantry of their time, had abandoned their period of splendor after their defeat at the Battle of Rocroi in 1643. Carlos II, the last Spanish monarch of the House of Habsburg, reigned. In spite of everything, the Hispanic monarchy conserved great part of its dominions in Europe and was a military power of the first order. Although Spain did not formally join the new Holy League, a host of some 12,000 Spanish volunteers responded to the call of the Pope, from nobles to simple people, including some veterans of Flanders such as Manuel López de Zúñiga -Duke of Béjar-, Antonio González, Donato Rodrigo de los Herreros, Mateo Moran, Felix de Astorga, Juan Manrique and other captains of Tercio, moved in some cases by the thirst for glory and adventure, and others encouraged by faith and desire to defeat the Turks, who from long ago they were among the worst enemies of Spain.

A Grande of Spain and veteran of Flanders as commander of the Spanish contingent

The story of Mr. Manuel López de Zúñiga is very special. He was a Grande of Spain, the highest rank of the Spanish nobility. Others would have stayed in court to enjoy such high distinctions, but Manuel did not. As Pedro Calderón de la Barca had written in 1650 in some famous verses about the Spanish army, "that nobody expects to be preferred by the nobility that he inherits, but by which he acquires". Being a man of deep religiosity and unaccustomed to the life of the court, and in spite of his ill health, in 1679, aged 22, he asked for permission to march to Flanders to fight. He was finally granted military employment in 1681, becoming Master of Field, receiving command of a Tercio.

There, Manuel demonstrated his courage as a strategist and also his courage as a combatant, gaining great fame during the Siege of Oudenaarde against the French. After the signing of the Regensburg truce in August 1684, Manuel asked the King for permission to return to Spain, but not because he wanted to get away from his military obligations. On the contrary: he had had knowledge of what happened at the Siege of Vienna the previous year, and was eager to join the Holy League to fight against the Turks, moved by his deep faith. Once obtained the license, he returned to Madrid in February 1685 and immediately began preparations to travel to Vienna, leaving there with his cousin Gaspar de Zúñiga and some of the veterans who had fought with him in Flanders. During his journey, in which Manuel made numerous charitable works, they took advantage of the Spanish Way, the old route used by the Spanish Tercios in their journeys between Milan and Central Europe, arriving in Vienna on June 12, 1686, being received there personally by the Emperor Leopold I.

An 'encamisada' in Hungary in the style of the Tercios de Flandes

The host of the Holy League, made up of some 100,000 men from a multitude of nations - soldiers from almost all of Europe, both Catholics and Protestants - left Vienna on June 14, 1686, arriving in the vicinity of Buda on the 22nd of that month. Although the attacking forces were far superior to the Ottoman garrison of the Hungarian city, it was very well protected by strong walls. The siege was bloody and caused numerous casualties among the besiegers. During the battle, the Spaniards participated in combats against the Turkish forces that carried out several incursions against the besiegers. On July 6, Manuel López de Zúñiga conducted an "encamisada" against the Turks, a typical operation of the Spanish Tercios in Flanders, which consisted of a surprise night attack. With a force of fifty Spanish and Italian volunteers, he attacked a palisade defended by janissaries (the elite force of the Ottomans), allowing the advance of the besiegers. The high risk run by Manuel accounts for the fact that he returned from this action with his hat punctured by a shot. The audacious action of the Spanish nobleman caused the admiration of the troops of the Holy League.

The first attack to the breach was headed by Spaniards

Finally, on July 13, the imperial artillery opened a breach in the walls. This was the decisive moment of every siege, because it allowed the penetration of the attacking troops into the wall. Leading the attack was an honor. The first to penetrate through the breach were 300 Spanish soldiers led by Manuel López de Zúñiga, demonstrating a courage that provoked admiration among their allies. Manuel had claimed that position for his own, following the tradition of the Spanish Tercios to claim for them the first positions in the fight, something they considered an honor. This first assault was met with a strong Turkish resistance, suffering the Spanish many casualties. López de Zúñiga was seriously injured by a bullet. He suffered a painful agony, during which he requested that he be excused to anyone he might have offended, and transmit his forgiveness to everyone who had offended him. He died three days after the attack. His body was buried in the College of San Ignacio in Gÿor (Hungary), and later repatriated by his brother Baltasar to Spain, being buried in the chapel of the convent of Our Lady of Mercy of Béjar. When that chapel disappeared, its remains were transferred to a niche in the cemetery of San Miguel in Béjar, where they rest today.

The heroic death of the Duke of Béjar caused a deep sorrow in the generalissimo of the host of the Holy League, Charles V of Lorraine. The relatives of the deceased even received letters of condolence from the Pope and Emperor Leopold I of the Holy Roman Empire. Exalted as a war hero, the figure of Don Manuel reached fame and glory at that time, a nobleman full of virtue and who abandoned the comforts of his rank to die in defense of the faith far from his land. Masses were dedicated throughout Spain, as well as poems and plays.

The final assault on September 2 also had Spaniards at the forefront

Despite the deep sorrow caused by the death of the Duke of Béjar, the Spaniards who had accompanied him to Hungary continued to fight. On July 22, a bomb launched by the Bavarian troops reached a Turkish powder keg, causing it to explode and causing numerous deaths to the defenders. Despite this, the resistance of the Ottomans remained fierce, causing many casualties to the attackers. At the beginning of August, both the attackers and the besiegers were already very damaged. Among the Turks they already had more wounded than unharmed soldiers, but they continue fighting with ferocity, especially the janissaries, who still dare to carry out an attack. At the end of the month, the besiegers of the Holy League received new reinforcements. Finally, on September 2 at two in the afternoon, the final assault was launched. Once again the Spaniards took the lead, leading the attack on the Bavarian side. A Hungarian chronicle reminds its leaders: "The Spaniards, Escalona, Llaneras, Valero, the Counts Zúñiga, Morán, Marín, Servent, Otaño, Manrique, Fernández Caballero, along with their aristocratic relatives, are at the head of the column of attack". That day, the forces of the Holy League defeated the Turks.

Two monuments remember in Budapest the Spaniards who fought there

To this day, the deeds of those Spanish volunteers have been practically forgotten in Spain, but not in Hungary. In 1934, a monument was built in Budapest to those 300 Spaniards who led the attack on the Beda breach. The monument is in the same place where the gap was opened. Under two shields of Spain (that of the Catholic Kings, with the Eagle of San Juan, and that of the Second Republic, which was the current regime in Spain in 1934), and under a coat of arms of Hungary, the monument includes this text in Spanish and in Hungarian: "The 300 Spanish heroes who took part in the Reconquest of Buda entered here". To its left, another more recent monument, installed in 2000 by the Regional Government of Catalonia, reminds the Catalans who participated in the Spanish expedition to Hungary, with this text in Catalan and Hungarian: "In memory of the Catalans who fought for the liberation of Buda."

P.S.: my thanks to the Hungarian citizen @MiklosCseszneky; thanks to him I had knowledge today of this ephemeris.

Bibliography:

- Buda ostroma, 1686 - spanyol szemme (in Hungarian)

- Historia del Buen Duque don Manuel de Zúñiga. Una actualización de la biografía del X titular de Béjar (1657 - 1686) / Emiliano Zarza Sánchez (in Spanish)

- Vida y muerte del XII Conde de Belalcázar D. Manuel Diego de Zúñiga Sotomayor y Mendoza / Blog del Ayuntamiento de Belalcázar (in Spanish)

---

(Main image: "The recovery of the Buda Castle in 1686", a painting by the Hungarian painter Benczúr Gyula, 1896)

|

Don't miss the news and content that interest you. Receive the free daily newsletter in your email: Click here to subscribe |

- Most read

- The Pegasus case and how it could end with Pedro Sánchez due to a decision by France

- The brutal 'touch and go' of a Lufthansa Boeing 747 at Los Angeles Airport

- The real reason for Sánchez's victimizing letter using his wife as an excuse

- The massive takeoff of more than half of the United States B-2 Spirit stealth bombers

- What did Morocco find in Pedro Sánchez's cell phone to humiliate him in this way?

- Sánchez's 'reflexion' gives way to a wave of leftist pressure on judges and media

- Lenin: numbers, data and images of the crimes of the first communist dictator

ES

ES

Opina sobre esta entrada: