Glory and Remorse: the Poles in the Spanish War of Independence

As a Spaniard who loves and admires Poland, so far I have tackled in this blog heroic episodes of the history of that country. Today I talk about a very thorny one that involved our two Nations.

The partitions of Poland and the creation of the Duchy of Warsaw

Poland had been one of the most important military powers of central Europe during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In 1683, the Polish King Jan III Sobieski and his famous winged hussars had been determinant in defeating the Ottomans during the Battle of Vienna, a key fact of European history (had that battle been lost, Europe would have been dominated by Islam ). However, in the 18th century the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth went into decline. In 1772 the First Partition of Poland took place: Russia, Prussia and Austria were divided several zones of the country. In 1792 came the Second Partition, and in 1795 the Third, with which Poland completely disappeared from the map. Many Poles then put their hopes to recover the independence of their Nation in revolutionary France, which had as enemies the powers that had divided Poland. This hope was strengthened in 1807, when Napoleon signed the Treaty of Tilsit with Russia, for which the Duchy of Warsaw was created, a satellite state of Napoleonic France that covered much of the territory that Poland had before the partitions.

The Polish Legions

Thousands of former Polish soldiers emigrated to France and Italy, forming the famous Polish Legions, who fought as allies of revolutionary France in the wars that followed from the Battle of Brescia (Italy), in 1797, until the Battle of Waterloo (today's Belgium) in 1815. Very appreciated by Napoleon and with a notable weight within the French forces (the only non-French Marshal of the Napoleonic Army was the Polish prince Józef Antoni Poniatowsk), the Polish soldiers fought in the service of France from Russia to Haiti, going through Spain. It was precisely in Spanish lands where the Poles in the service of Napoleon reached their greatest glory, although the campaign also meant for them very hard times and certain repairs, as they fought for the dreamed independence of their Homeland by supporting some Frenchmen who had invaded an independent Nation as Spain.

A Polish lancer takes a Spanish prisoner in the Battle of Somosierra. Painting by the Polish painter Juliusz Kossak (1891).

A kind of great national remorse

As Jan Stanislaw Ciechanowski explained in "The Polish vision of the War of Independence" (published in 2006 the magazine "El Basilisco"), "the intervention in Spain became on the one hand one of the many symbols of the successes of Polish weapons, and on the other hand, in some circles, in a kind of great national remorse", noting that in their memoirs, most of the Polish veterans of the Spanish War of Independence agreed that "they fought against a people defending their freedom and independence." Ciechanowski explains, in fact, that some Polish soldiers "recognized the cause of the Spaniards by resigning and asking for transfers, such as Captain Michal Wyganowski and Colonel Feliks Potocki, chief of the fourth infantry regiment." Often these resignations - and also some desertions - were provoked by the Spanish calls to the Poles. Ciechanowski translated a Polish text published by Józef Załuski in his book "Wspomnienia" (1976), about a proclamation directed by the Spaniards to the Poles who served with Napoleon:

"Poles, abandon your colors, crimson and white, colors of honor and without blemish. You, deprived of liberty, invade a foreign country, Catholic like yours, to plunge it into slavery."

The well-deserved prestige of Polish soldiers

Napoleon sent 20,000 Poles to Spain, among them horsemen of the Imperial Guard, the First Regiment of Light Cavalry, the Division of the Duchy of Warsaw (with three regiments of infantry) and the Legion of the Vistula (with a regiment of Ulanian spearmen and three infantry regiments), a force composed of veterans of the Polish Legions who had gained much experience in the fight against the guerrillas in Italy. These forces demonstrated in Spain that the prestige of the Polish soldiers was not free. The Legion of the Vistula became famous in the two Sieges of Zaragoza (1808 and 1809). At the Battle of Fuengirola (1810), a small force of 200 Polish gunners headed by Sergeant Józef Zakrzewski was able to defeat an Anglo-Spanish force that exceeded him by a ratio of 10 to 1.

Poles and Frenchmen on the summit of Somosierra, with the Spaniards who took prisoners. Picture "The pass of Somosierra" by the French painter Horace Vernet.

The heroic cavalry charge of the Battle of Somosierra

But without a doubt, the most remembered and more surprising fact was the starring by the Third Squadron of the First Regiment of Light Cavalry, composed of 150 horsemen led by Jan Kozietulski: on November 30, 1808 they charged up the hill in the Battle of Somosierra, facing the artillery and the Spanish infantry, and achieving reach the top with many casualties. This burden is remembered today as one of the greatest feats in the history of universal cavalry, and by that action Kozietulski was distinguished by Napoleon with the Legion of Honor. A plaque remembers today in Somosierra the Spanish and Polish fallen in that battle.

Polish riders in a reenactment of the Battle of La Albuera in 1811 (Photo: Arsenal.org.pl).

The displeasure of the Poles towards the atrocities of the French

Of course, not all that war was heroic. The French occupiers treated the Spanish population with great cruelty, staging all kinds of crimes, pillages, robberies and profanations. Kajetan Wojciechowski, lancer of the Legion of the Vistula, remembered some time later in his memoirs about the atrocities committed by the French after his victory in Zaragoza: "The palaces, churches and convents were in ruins ... of the old greatness nothing remained, apart from the hatred without limit to the French, which the Spanish agonizing left their children instead of a blessing!" Far from censuring the hatred of the Spaniards, Wojciechowski understood: "And how the Spanish nation would not have reason to swear revenge to the French?", he asked. Faced with the atrocities committed by the Spaniards against the French as revenge, the Polish officer added that "the French, with their impiety, debauchery and indiscipline at the time, deserved them".

Catholicism was a meeting point between Spaniards and Poles

Polish soldiers, coming from a deeply Catholic country, especially disliked the desecration and looting of French soldiers against churches and monasteries. The Poles came to stand up to their allies when the French tried to loot a church in Alcalá la Real (Jaén), in 1810: the Slavs defended the temple. The Catholic religiosity of the Poles also drew attention to the inhabitants of Madrid, because unlike the French (trained in secularism and irreligiosity emerged from the Revolution of 1789), the Poles went to churches and prayed often, that made the Spaniards look at them with more benevolence than the French. Ciechanowski points out, in fact, that many Poles were saved by carrying crucifixes or medals of the Virgin hanging around their necks, or by praying in death, because the Spaniards had no compassion for French prisoners, but those gestures of piety made them forgive the lives of many Polish prisoners. Such was the case of Lieutenant Joachim Hempel, a Polish lancer wounded in the Battle of Medina de Rioseco (1808). Upon seeing his Polish uniform, which knew how to pray in Latin and had a scapular hung around his neck (a young Spanish woman had given it to him), one of his captors shouted: "Leave him alone, he is a Pole!" The Spaniards spared his life and took him to a Dominican convent near Valladolid.

Picture "Charge of cavalry in the valley of Somosierra", by the Polish painter Wojciech Kossak.

Helping in childbirth and protecting women

There were facts that contributed considerably to improve the image of the Poles among the Spaniards. Ciechanowski cites the help of the Slavs to a Spanish parturient during the attack on Burgos, and another similar case in Briviesca (Burgos), where a Polish officer who helped in a childbirth became godfather of the newborn, giving the officer to the mother of the child two religious images. The aforementioned Lieutenant Hempel saved a son of a Grande from Spain near Burgos, drowned in a stream. The protection that the Poles gave to the women and their properties were received with gratitude. Count Tomasz Łubieński, one of the protagonists of Somosierra's charge, recalled that when they arrived in Orduña (Vizcaya), he ordered the seizure of the property of the villagers, but when he learned that the seized property was one of the poorest of the place, he ordered them returned, receiving "gratitude and blessings" difficult to describe. In his memoirs he wrote about Spaniards: "At least I could never complain about them, and although they did not always welcome me, they never did it badly, after a few days of getting to know each other better, we always said goodbye to the new acquaintances." Ciechanowski cites the case of a priest of Saragossa who tried to strengthen ties of friendship with a Polish officer of the lancers of the Vistula Legion, Kajetan Wojciechowski, saying:

"Why are the Poles of the same religion as the Spaniards, nevertheless their enemies? If we have ever invaded your country, taken your property and destroyed your importance? Say it clearly, why do you sacrifice yourselves for the cause of others? So blind you can not fit comfortably in your land, that you look for bread where the French? Then come to our house, we will give you bread and you will be our brothers".

In all sincerity, the Polish officer recalled: "It was difficult to respond to the sincere words uttered by the elder."

Polish riders talking to a Spanish compatriot during a reconnaissance mission. Painting by the Polish painter Juliusz Kossak (1875).

The defamations of the French towards their own Polish allies

Paradoxically, much of the bad reputation that the Poles had among the Spaniards of that time was extended by their French allies. Ciechanowski explains that in Lorca (Murcia) a French soldier entered a house and raped the owner's daughter. He protested to General Horace François Sébastiani, chief of the Fourth Corps of the French Army. This, despite knowing that the defendant was a Frenchman, by the description given by the girl, called the Polish Colonel Jan Konopka, "admonishing him and accusing the Poles of being looters and rapists, which was going to force to the inhabitants to the uprising,", Ciechanowski says. "The Slavic official, touched in the liveliest, ordered to appear to the regiment, but the Spanish girl did not recognize the culprit and when he saw the Poles he declared that his criminal had been a Frenchman." Ciechanowski also tells another anecdote occurred on the road from Lorca to Seville, when Colonel Konopka and his wife went to dinner at the house of a Spanish magnate. The wife of the Polish officer was surprised to see that her hosts did not introduce them to their children. The lady of the house recognized, between vacillations, that the French had told them that the Poles were looters, that they destroyed everything and that they were Asians who ate children. The defamation of the French against their own allies meant that when they arrived in Seville, a delegation from the city asked Marshal Soult that the Poles remain outside the city.

The testimonies of the Poles about the French crimes of May 2, 1808

After the years, the atrocities committed by the French in Spain still filled with horror the Poles who had fought in that war, especially the executions of Spanish women and children. Unlike the French, the Poles tried to treat Spanish prisoners well, and even managed to save some from being shot by the French. On some occasions they came to pay tribute to the captured Spanish officers. In spite of this, the cruelties committed by the French, and replicated by the Spaniards, were the dominant note in that bloody war. A Polish rider, Wincenty Placzkowski, recalled in his memoirs that the origin of this hatred was in the massacre of May 2, 1808 in Madrid, stating that it was then that the Spaniards "became our worst enemies." The rider recalled the brutalities that day: "It was a horrible image, what a weeping and lamentations! ... The parents look for and recognize their children, the children their parents. The husband looks for his wife, the husband, friend to other friend, it is difficult to describe these moments, result of inhuman tyranny!" The Polish lancers participated in those events, but Captain Józef Bonawentura Zaluski recalled that the sympathy between Poles and Spaniards was consolidated after that date, because while the French and the Mamluks used their weapons against the Madrilenians, the Poles had refused to use yours against the people.

Polish recreators of the 4th Infantry Regiment of the Duchy of Warsaw (Photo: Dobroni.pl)

The admiration of the Poles for the courage of the Spaniards

As for the opinion that the Poles had about the Spaniards, it was very different and often depended on the very situation of the Slavic soldiers in this contest. Without a doubt, the worst opinion was taken by the prisoners of war. However, there were many cases of remorse for having fought those who fought for the independence of their homeland. The aforementioned Polish Lieutenant Lieutenant Joachim Hempel considered that the war against the Spaniards had been "unjust". Second Lieutenant Andrzej Niegolewski, who had fought in the heroic charge of Somosierra, acknowledged in his memoirs that the Spaniards "fought for the sacred cause, that is, the cause of their independence." Deydery Chlapowski, Napoleon's aide-de-camp, praised the Spaniards: "Every one of them, even if he was wounded or discarded, stood up until the last blow, which proves that he is a brave nation." However, Chlapowski distinguished between the value of the common people and the attitude of his nobility: "I have met many Spanish gentlemen and I considered that just as the people are brave and willing to sacrifice, the great ones (the high nobility) are effeminate." The lancer lieutenant Jan Chlopicki remembered in his memoirs a Spanish heroine, called Camila, "who like the Virgin of Orleans, carried away by the ardent love of the country, humming war songs, with the banner in hand, inflamed the soldiers with courage."

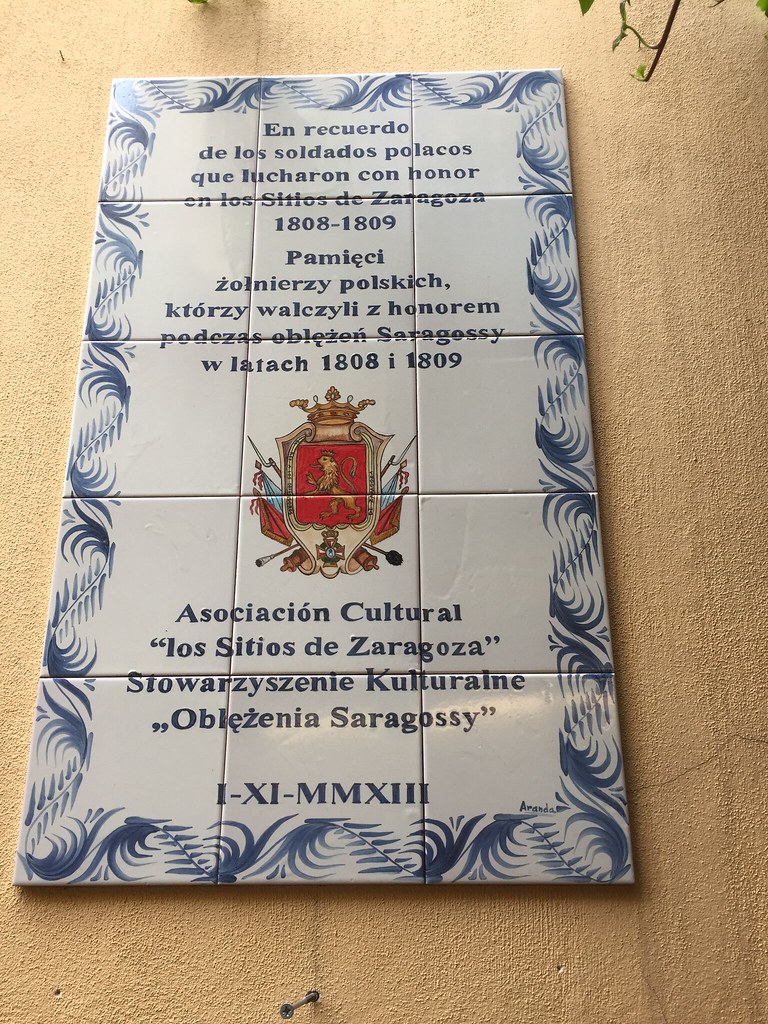

A photo that a reader send me. Plaque inaugurated in Zaragoza on November 1, 2013 by the Cultural Association "Los Sitios de Zaragoza", in homage to the Poles who fought there. The plaque says in Spanish and Polish: "In memory of the Polish soldiers who fought with honor in the Sites of Zaragoza 1808-1809".

The memory of that war in today's Poland

With the defeat of Napoleon in 1815 the Duchy of Warsaw also came to an end. Significantly, one of Poland's most famous national heroes, Tadeusz Kościuszko, a veteran of the American War of Independence, refused to join the Polish Legions because he disliked Napoleon's dictatorial character and did not believe that the French Emperor would seriously support the sovereignty of Poland. Kościuszko believed that Bonaparte had created the Duchy of Warsaw as a mere source of resources for his Army, something in which he was not entirely wrong: the Duchy came to have a force of 100,000 men, a very large army for a territory with 4.5 million inhabitants. Much of these forces were decimated in Napoleon's campaigns, leaving the Duchy seriously damaged and economically bankrupt. In spite of this, even today Napoleon is still admired in Poland, perhaps even more than in France, because the Poles consider him as a powerful defender of his independence. The national anthem of Poland, the Dąbrowski's Mazurka, is the only national anthem in the world that quotes Bonaparte, specifically in his third stanza:

"We'll cross the Vistula, we'll cross the Warta,

We shall be Polish.

Bonaparte has given us the example

Of how we should prevail."

At the Warsaw Uprising Square in Poland, a bust dedicated to the French Emperor was inaugurated in 2011, a work of the sculptor Michał Kamieński. The location of the monument is not accidental, since between 1921 and 1957 that square was named Napoleon Square.

Serve this entry as a tribute to the Spaniards and the Poles who fought with honor in the War of Independence.

Spanish, Polish and French reenactors pay homage to the fallen in the Battle of Somosierra, in 2016 (Photo: Asociación Histórico-Cultural Poland First to Fight).

Bibliography:

- "La visión polaca de la Guerra de la Independencia", by Jan Stanislaw Ciechanowski. Published in 2006 the magazine "El Basilisco".

- "Soldados polacos en España. Durante la Guerra de la Independencia Española (1808-1814)", by Fernando Presa González, Grzegorz Bąk, Agnieszka Matyjaszczyk Grenda and Roberto Monforte Dupret.

---

(Main imagen: Picture 'The Battle of Somosierra' by the Polish painter January Suchodolski, 1860).

|

Don't miss the news and content that interest you. Receive the free daily newsletter in your email: Click here to subscribe |

- Most read

- The 'hole' without civil flights around Paris during the opening of the Olympic Games

- Spain vetoes the Russian frigate 'Shtandart', which intended to reach Vigo, in all its ports

- The interior of the Statue of Liberty torch and the sabotage that canceled its visits

- The ten oldest national flags in the world that are still in use today

- The BNG boasts of the support of a terrorist group and a dictatorship at a public event

- The Russian intelligence document that sparked a hoax about French troops

- A virtual tour of ancient Rome in full color, just as it was in its heyday

ES

ES

Comentarios:

Jonathan North

You might be interested in this e-book which has just been published:

http://www.jpnorth.co.uk/publications/books-napoleonic-and-french-revolution/glory-and-despair/

It presents four Polish accounts of the bloody sieges of Saragossa and reveals much about the state of mind of Poles, who enlisted to liberate their own country, pitted against enemies who were striving for their own independence.

17:25 | 24/10/18

Opina sobre esta entrada: