Poland and Spain: the historical links between two great Nations of Europe

November 11 is a special day, not only because we remember the end of the First World War in 1918, but also because that day Poland regained its independence.

Today Poland celebrates the 100th anniversary of the recovery of its national independence. In addition to congratulating all the Polish friends of Counting Stars on this day, I would like to take this opportunity to show the many links that have united our two great nations in history.

Two Nations with Catholicism as a sign of identity

The history of the Polish people is intimately linked to the Catholic religion. The first monarch of the Poles, Duke Mieszko I, was baptized in the year 966 and with him his people, formerly pagan, converted to Catholicism, adopting it as one of his hallmarks as a Nation (the Visigoth King Recaredo I had made the same in Spain in the year 589). Undoubtedly, the religious aspect is in which Poland and Spain have more similarities. The two nations have as their patron saint the Immaculate Conception, for which both peoples have professed a lot of devotion, and that was the protagonist of an appearance in the Poland then occupied by Prussia in 1877.

Likewise, in both countries there is a great devotion for St. James Apostle: at the end of the 18th century there were already 155 churches in Poland dedicated to the saint. In Poland there were already pilgrimages to Santiago de Compostela in the Middle Ages, through the so-called High Road, which passes through the Polish cities of Gdansk and Szczecin. In Spain documentation is preserved about the arrival in the fourteenth century of Polish pilgrims such as Estanislao de Vedereke, Francisco de Schubyn, Clemente de Mocrsco and Jacobo Cztan de Rogow. The devotion to St. James in Poland was revived again in the 20th century by the Polish Pope St. John Paul II on the occasion of his visits to Santiago de Compostela in 1982 and 1989. Incidentally, Pope Woytyla professed a great love for Spain, which he called "Land of Mary". He visited it five times, being one of the five countries he traveled the most during his pontificate. Currently, in the Mount of Gozo, near Santiago, there is a Pilgrimage Center that is called "John Paul II" and that is attended by a Polish priest, Father Roman Wcisło, a man born in Polish Galicia and who now he develops his pastoral activity in Spanish Galicia.

The refuge of the Jews expelled from the rest of Europe

Poland was for a long time a refuge for religious tolerance in Europe. The Jews had been progressively expelled from the rest of the continent: France (1182), England (1290), Austria (1421), Spain (1492), Sicily (1493), Lithuania (1495), Portugal (1497), Navarre (1498) ... But they found a refuge in Poland, which ended up hosting the largest Jewish community in Europe. In the middle of the sixteenth century, 80% of Jews from all over the world lived in Poland. Some Spanish Jews, known as Sephardic ("Sefardyjczycy", in Polish), settled in southern Poland, in a region whose name coincides with that of a Spanish region: Galicia.

Poland and Spain: two countries that have never declared war against each other

In the 16th century Poland established diplomatic relations with the Spanish Monarchy, under the guidance of Jan Dantyszek, known in Spain as Juan Dantisco. The two nations maintained friendly diplomatic relations between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. Despite the fact that the history of Europe has been plagued by wars (both Poland and Spain have been at war with all their neighboring countries, except the Principality of Andorra), there is a curious circumstance: both Nations have never They have been at war with each other, not even in opposing coalitions, although sometimes subjects of both countries did fight on enemy sides as volunteers.

A Polish King, son of a Hispanist, who saved Europe from a Turkish invasion

Another of the similarities between Poland and Spain has been their status as nations defending the borders of Christianity, with the Reconquista in the Spanish case and with the fight against the Turks in the Polish case. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Commonwealth formed by the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was one of the great powers of Central Europe. In 1683 the winged hussars of the Polish King Jan III Sobieski were decisive in the defeat of the Ottomans at the Siege of Vienna. If it had not been for them, the Muslim Empire would have spread throughout Central Europe and perhaps today Christian Europe would be no more than the shadow of what it is. It is a victory that all Europeans have to thank our Polish brothers. And a curious fact: the father of that Polish King, Jakub Sobieski (1590-1646), was a famous Hispanist and made a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela in 1607, visiting Pamplona, Estella, Oviedo and Padrón, as well as the city of the Apostle, which It left him amazed.

Maria Amalia de Saxony: a Polish Queen for Spain

In 1738 Spain and Poland had a particular approach by marriage: that was the year in which a man born in Madrid, the then King Charles VII of Naples and future Charles III of Spain, married a Polish princess: Maria Amalia de Saxony, the fourth daughter of the then King of Poland, Augustus III, and of Maria Józefa Habsburżanka, daughter of the Emperor Joseph I of Habsburg. Although it was an arranged marriage, both ended up being a happy couple and Charles was very much in love with Amalia, whom he considered an angel. The King was always faithful to her and he never had lovers (something uncommon at the time). They had no less than thirteen children: the sixth of them became King Charles IV of Spain. Sadly, she died a year after arriving in Madrid, in September 1760, because of tuberculosis. The Spanish monarch confessed: "In 22 years of marriage, this is the first serious disgust Amalia gives me." Very affected by the death of Amalia, Charles III never remarried again. The remains of that Polish Queen of Spain rest today in the Pantheon of the Kings of Spain in the Monastery of El Escorial.

Only one Nation protested against the Partitions of Poland: Spain

Regrettably, internal divisions weakened the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 18th century. In 1772 Russians, Austrians and Prussians agreed to divide a part of the territory of Poland, beginning a progressive dissolution of the country. Only a European monarch protested against this affront to the Poles: King Charles III of Spain. The Second Partition of 1793 left Polish territory halved. Finally, in 1795 the Kingdom of Prussia, the Austrian Empire and the Russian Empire divided up what was left of the country, erasing Poland from the map for 123 years. One of the last ambassadors that left Poland after his disappearance was that of Spain, Domingo de Iriarte.

The Polish cavalry in Spain: from the War of Independence to the First Carlist War

Trusting that Napoleon would help them regain their independence, many Poles supported the French Emperor and ended up fighting in Spain's War of Independence against the Spaniards. The Polish cavalry reached in Spain one of its most amazing victories, with its reckless charge in the Battle of Somosierra. Despite being enemies, Poles and Spaniards had a curious relationship in that war, about which I spoke here.

After the defeat of Napoleon, the Poles did not sit idly by. On November 29, 1830, the so-called November Uprising broke out in Warsaw against Russian rule in the eastern part of ancient Poland. This revolution led to a war that lasted almost a year and ended with the defeat of the Poles, after which many of them left for France. Some ended up enlisting in the Foreign Legion, founded in 1831, and that's how a Polish Lancers Regiment ended up fighting again in Spain, this time during the First Carlist War (1833-1840), with the supporters of Isabel II. In Poland there were more uprisings in 1846, 1848 and 1863. The indomitable spirit of the Poles was even reflected in an uprising in 1866 by 700 Poles who had been deported to Siberia by the Russians.

With regard to the Polish Uprising of 1863, the Spanish historian Joaquín Albert de Alvarez wrote the following in his book "Revolution of Poland", published in Barcelona that same year: "In Spain, the quintessential nation, the cause of Poland has inspired perhaps a feeling of more general interest, than in any other nation in Europe," and he added: "Is not there some affinity between the Polish revolution of 1863 and the Spanish revolution of 1808? ... How the descendants of the heroes of 2 May they have to stop sympathizing with the brave sons of Kosciusko? It is impossible not to love two nations that have gone through similar tests and that have wielded weapons in ill-fated times driven by the same sentiment."

Spanish diplomacy in Poland before the recovery of its independence

Significantly, although Poland had ceased to exist as an independent country, Spain maintained a Consulate in Warsaw between 1878 and 1913, which was occupying various venues. After the recovery of the independence of Poland, the country reestablished its diplomatic relations with Spain on May 30, 1919, installing the first Spanish diplomatic delegation at the Bristol Hotel in Warsaw. Months before, a Polish Delegation was already operating in Madrid, they are located at number 4 Marqués del Riscal Street, which provided documents to Poles living in Spain.

The Polish-Soviet War: a prophetic telegram in a Spanish newspaper

One of the most decisive - and at the time most forgotten - conflicts in the history of Europe took place between 1919 and 1921: the Polish-Soviet War, which was the first international conflict provoked by communist expansionism. Although Spain was far from the theater of operations, the Spanish press followed the evolution of hostilities on a daily basis. On August 12, 1920, with the Bolsheviks at the gates of Warsaw, the Abc newspaper of Madrid published a prophetic Polish statement received by telegram in the city of San Sebastian: "If today the freedom of Poland is in danger, tomorrow others will be endangered many peoples, for the victory of the Bolsheviks on the banks of the Vistula would be a serious threat to Western Europe. A new world war, in the opinion of the Polish Council, looms over peoples who do not hear the voice of humanity, of truth and justice. If those people are afraid to go to war, the war will go to them as it has gone to Poland, and they will find themselves without means of defense against the attack." The telegram ended with the warning that "on the banks of the Vistula today more is decided, much more than the fate of Europe." In spite of the warnings, Poland remained practically alone, but against all hope the Poles managed to defeat the Soviets coinciding with the day of the Assumption of Mary, on August 15, something that in Poland was seen as a miracle. On August 20, Abc gave news of the Polish counter-offensive.

The Poles and the Spanish Civil War

During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), one of the International Brigades that fought on the Republican side, the 150, was composed mostly of Polish communists. In Poland they are known as the "Dąbrowszczacy", but they do not have a good memory of them because their leader, Karol Świerczewski, had been a traitor to Poland (he fought alongside the Bolsheviks in the Polish-Soviet War), and after the Second World War collaborated with the communist dictatorship established by Stalin, dictating 68 death sentences for political reasons.

During the Spanish War, Poland sold arms to both sides, from rifles and grenades to tanks and planes. The struggle divided the Polish society: the right wing felt identified with the national side -especially by its Catholicism-, and the left wing felt sympathy for the Republicans. In Madrid, the Polish ambassador to Spain was Marian Szumlakowski, akin to the national side. The Embassy of Poland granted diplomatic immunity to the home of the Marquis of Ybarra, turning it into a "Polish Home" that gave asylum to some four hundred people persecuted by the Popular Front, among them the famous doctor Gregorio Marañón.

Spain before the German invasion of Poland

After the hostilities ended in Spain, Franco's government was upset by the pact signed by Germany and the USSR in August 1939. Franco conveyed to Philippe Pétain, then ambassador of France in Madrid, that this pact liberated Spain from all obligation to Germany (remember that Hitler had helped the national side in the Spanish Civil War). Relations between Spain and Germany cooled. At that time references to Poland appeared in the Spanish press, pointing out the similarity between the two countries for their Catholicism and for having defeated communism (Poland in 1920 and Spain in 1939).

When Germany invaded Poland and World War II broke out, Spain declared itself neutral. However, in Spanish society there were expressions of sympathy with Poland. Even the Falangist newspaper "Arriba", one of the regime's media, came to praise "Polish heroism" without criticizing Germany. Franco came to recognize on September 29, 1939 that he had made "persistent efforts" to prevent the collapse of a nation, in clear reference to Poland, "fulfilling the duties imposed on us by fidelity to our history and Spanish Catholic thought." The Soviet invasion of the eastern part of Poland on September 17 had caused unrest in Spain and increased Spanish sympathy for the Poles.

Polish soldiers fled to Spain after the surrender of France

After the surrender of France in May 1940, many Poles who had come to that country to continue fighting managed to flee to Spain through the Pyrenees. The Polish Consulate General in Barcelona, faithful to the Polish Government in exile, played an important role in welcoming these soldiers. "The employees of the consulate, often personally, picked them up in small towns in the Pyrenees, where they had been taken by paid guides. There they were given false documents and in the end they sent them to Great Britain," the Consulate explains on its website. It adds: "In 1941 the Polish Government in Exile and the Polish Red Cross in London allocated the necessary means to create a clandestine organization with a network of trusted guides that took the refugees directly to Barcelona and looked for safe hiding places in them. the city. On many occasions, these hiding places turned out to be the offices of the consulate on Fontanella Street or the private floors of their employees." However, "a significant number of Poles who had crossed the Pyrenees fell into the hands of the civil guards, and ended up in the border prisons in Sort, La Seu d'Urgell, Puigcerdà, Figueres, etc. The Honorary Consulate tried its best to get them out of there or at least improve their living conditions in prisons."

The situation of the Polish soldiers who were interned in Spain was complicated by the pressure of the German authorities, and specifically the Gestapo, to the Franco regime. Because of this a concentration camp was built in Miranda de Ebro (Burgos) to confine military refugees of all nationalities, including Poles. In 1942, two Poles who participated in the refugee support network of their country, Karolina Babecka and Mavis Bacca, were accused of espionage and imprisoned in the women's prison of the Cortes, in Barcelona. Babecka was released a month later thanks to her father's contacts. Bacca was released after the intervention of the Polish Embassy in 1943.

A Polish warship that sank a Spanish fishing vessel

Another clash between Spaniards and Poles in the Second World War was caused by the blockade that Allied warships imposed on the Spanish coasts of the Cantabrian Sea. Despite the fact that Spain was a neutral country, several Galician fishing vessels were sunk by Allied vessels after entering waters that had been blocked from sailing by the British Admiralty. The Polish destroyer ORP Orkan participated in this siege, which is known to have sunk the Galician fishing vessel from Vivero (Lugo), after taking over its crew, on July 22, 1943. The allies believed that the Galician fishermen were carrying out espionage work for the Germans. The Spanish press never reported these sinkings, because of censorship, in an attempt to maintain neutrality at all costs after the German defeat in Stalingrad marked a turning point in the war and led to a progressive distancing between Spain and Germany.

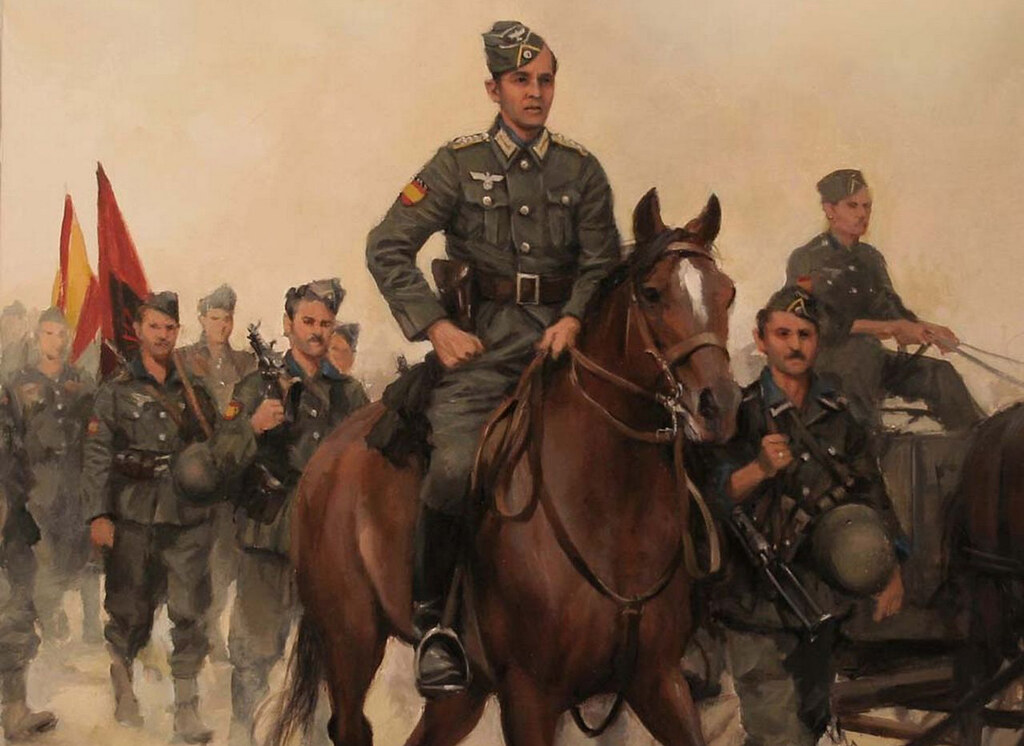

The deep memory left by the Blue Division in Poland

Although Spain did not participate as a belligerent Nation in the Second World War, after the German invasion of Russia in 1941, thousands of Spanish volunteers enlisted as volunteers in the German Army to fight communism, in revenge for Stalin's support for the republican side in The spanish civil war. This expedition received the approval of General Franco's regime. They formed a Spanish unit in the Wehrmacht, the 250th Infantry Division, better known as the Blue Division. At the end of the summer of 1941, a total of 17,909 Spanish volunteers arrived for several weeks aboard 128 trains to the Polish city of Suwałki, where they were concentrated and then walk 900 kilometers to the city of Vitebsk, Belarus, because the Germans did not want to provide them with trucks for that displacement.

According to Tasior Dariusz, the "southern temperament" of Hispanics made them still remembered by the oldest residents of the Polish towns of Suwałki, Raczki, Cimoch and Sejny. The Spaniards sympathized with the Poles and defended them against the abuses of the Germans. In addition, they attended with the Poles Sunday Mass at the Cathedral of St. Alexander in Suwałki, and were surprised to see that the Poles were such a religious nation and also, Catholic, because the propaganda had given them to understand that the Communists dominated Eastern Europe. The Spaniards even won the hearts of Polish women, explains Dariusz, who adds: "to this day in the Suwałki region you can meet people in whose veins partly Spanish blood flows." Dariusz writes that in Poland "the Spaniards left something very valuable. They proved that you can remain a man in war. This is evidenced by his favorable attitude towards the Poles, but also towards the Soviet population and the prisoners of war. Only his German uniforms caused a certain distance, which disappeared after some gestures and shouts of "Polaco" or "Viva Polonia". Thanks to this attitude, the oldest inhabitants of the Suwalki region, remembering the "bearded and mustached" soldiers of Spain, smile kindly."

Spain, one of the last supporters of the Government of Poland in exile

Although Poland had been erased from the map, in 1939 Spain recognized the Polish Government in exile, based in London, and in Madrid the Polish Embassy remained open throughout the war. Between 1948 and 1950 a Spanish diplomatic delegation operated at the Poland Hotel in Warsaw, but official relations between the two countries broke down, as the Polish communist dictatorship did not recognize the government of General Franco. Spain was the penultimate country to withdraw its recognition to the Polish Government in exile, in 1969 (the Allies had withdrawn it in July 1945, the last State to withdraw it was the Vatican on October 19, 1972). Until that year a delegation of the Polish Government in London functioned in Madrid as an official representation of Poland, headed by Józef Potocki, and an Honorary Consulate in Barcelona.

Polish exiles in Spain

Between 1949 and 1975 Radio Nacional de España broadcast programs in Polish aimed at the Polish colony in our country - formed in part by Poles exiled because of the Communist dictatorship - but also directed to Poland, where these broadcasts came to have some influence on Public opinion. The first director of these programs was Karol Wagner Pieńkowski. The exiled Poles in Spain were grouped especially around Catholic parishes, sometimes with their own chaplains, and had the help of the Polish Red Cross and the Association of Aid to the Poles, both with a delegation in Spain. The Polish colony also took care of the teaching of their native language to the Polish children: between 1947 and 1956 a Polish Public School for that purpose worked in Barcelona. In addition, between 1955 and 1969 the Polish Red Cross published in Spain the magazine "Polonia", directed by Juliusz Babecki and among whose subscribers was General Franco.

Diplomatic relations between Poland and Spain since 1969

On July 15, 1969 Spain and the People's Republic of Poland (name given the communist dictatorship) signed an exchange of notes on establishment of consular and commercial representations, establishing consular delegations of both countries in Warsaw and Madrid. The Polish delegation in Madrid was inaugurated on April 21, 1970. The Spanish delegation in Warsaw was organized on the delegation that had created there in 1964 a Spanish public body, the Spanish Institute of Foreign Currency. The reestablishment of diplomatic relations between Spain and Poland was signed on January 31, 1977, after the death of General Franco.

Relations between Poland and Spain today

According to the latest data from the Spanish National Institute of Statistics (INE), there are 1,845 Spaniards currently residing in Poland, divided among 1,250 men and 595 women. Also according to INE data, in January 2018 there were 52,212 Poles residing in Spain. In this case, the population of women exceeds that of men: 30,330 compared to 21,882.

To this day, Poland and Spain are member countries of the European Union (although Poland is not in the euro zone) and NATO. Currently, the Slavic country is one of the few that periodically hold annual summits with Spain at the level of presidents of the Government. As for the diplomatic representations, in addition to the Embassy in Madrid and a Consulate General in Barcelona, Poland has Honorary Consuls in Valencia, Murcia, Vigo, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Pamplona and Malaga. The diplomatic representation of Spain in Poland is more modest: in addition to the Embassy in Warsaw, there are Honorary Consuls of Spain in Gdansk and Wrocław.

In 2016, the total volume of bilateral trade between both countries was 9,816 million euros (4,810 million euros in Spanish exports to Poland, and 5,006 million euros in Polish exports to Spain). In terms of cultural relations, the Polish Institute of Culture operates in Madrid, and in Poland there are two delegations of the Cervantes Institute, one in Warsaw and one in Krakow, as well as seven examination centers to obtain the diplomas of Spanish: in Warsaw, Krakow, Wrocław, Poznań, Częstochowa, Ka-towice and Brzeszów. In addition, Spain is currently the second tourist destination preferred by the Poles (the first is Greece).

In the associative field, there are associations of Poles in various Spanish cities (you can see the list here): Madrid, Alcalá de Henares, Colmenar Viejo, Getafe, Móstoles, Vicálvaro, Ávila, Zaragoza, Cadrete (Zaragoza), Ceánuri (Vizcaya), Oviedo, Santiago de Compostela, Fuengirola (Malaga), Adeje (Tenerife), Murcia and Valencia. In addition, in Spain there is an association of Spanish and Polish, Poland First to Fight, which recreates the participation of Poles in World War II, in addition to addressing other issues related to the history and culture of Poland. In turn, in the Slavic country there is an association of Polish re-enactors, the Grupa Rekonstrukcji Historycznej Guerra Civil Española, which is dedicated to staging the Spanish Civil War in Poland.

Bibliography:

- "España ante la invasión alemana y soviética de Polonia en septiembre de 1939", by Bartosz Kaczorowski (in Spanish).

- "Błękitna Dywizja na Suwalszczyźnie", por Tasior Dariusz (en polaco).

- "Sefardyjczycy", en Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich (en polaco).

- "Armas polacas en la Guerra Civil Española", by Alberto Gómez Trujillo (in Spanish).

- "Polonia y Cataluña. Las relaciones diplomáticas durante los años 1918-1969". Consulate General of the Republic of Poland in Barcelona (in Spanish).

- "República de Polonia". Diplomatic information office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Spain (in Spanish).

- "Operación Mosquetero contra pesqueros gallegos", by Eduardo Rolland (in Spanish).

- "Polonia". Xacopedia (in Spanish).

- "España y la Europa oriental: tan lejos, tan cerca", by Carlos Flores Juberías (in Spanish).

- "Esteban Hoenigsfield, el ángel polaco de la glorieta de Rubén Darío", by Inés Martín Rodrigo (in Spanish).

- "María Amalia de Sajonia, la joven esposa del 'rey enamorado'", by Roberto Fernández (in Spanish).

- "La Polonia del Mediodía: un tópico polaco en la historia española", by Juan Fernández-Mayoralas Palomeque (in Spanish).

- "Extranjeros en la Primera Guerra Carlista", in the Historia de Iberia Vieja magazine (in Spanish).

|

Don't miss the news and content that interest you. Receive the free daily newsletter in your email: Click here to subscribe |

- Most read

- The Pegasus case and how it could end with Pedro Sánchez due to a decision by France

- The brutal 'touch and go' of a Lufthansa Boeing 747 at Los Angeles Airport

- The real reason for Sánchez's victimizing letter using his wife as an excuse

- Portugal confirms that it has begun its transition to the F-35 and indicates bad news for Spain

- The deployment of Spanish soldiers of the Regulars and BRILAT near Russian territory

- The ruins of the old Yugoslav radar station at Gola Plješevica, Croatia

- The ten oldest national flags in the world that are still in use today

ES

ES

Opina sobre esta entrada: